Ceramic Phone

Everyone seems convinced that the next-generation iPhone will feature a high-durability ceramic back. After researching technical information about the available materials, it turns out that such a choice would be quite impractical.

Ceramic: a dream or a disaster?

This is what Gizmodo says about the back of their stolen next-generation iPhone prototype:

[…] entirely flat [back], made of either glass (more likely) or ceramic or shiny plastic in order for the cell signal to poke through. Tapping on the back makes a more hollow and higher pitched sound compared to tapping on the glass on the front/screen, but that could just be the orientation of components inside making for a different sound.

John Gruber mentions Apple’s patent filing for ceramic enclosures, and touts ceramic as “[having] glass-like appearance and feel but [being] far stronger and more scratch resistant.”

I still have the first-generation iPhone with aluminium back, which is far more durable than glass or plastic. Of course, it’s impermeable for radio signal, so it has to be complemented with a plastic window. A shiny ceramic back with aluminium’s high-durability, but transparent for radio, would seem like a perfect solution. But it is not for the following reasons:

- Ceramic materials are very hard (scratch-resistant), but brittle. (Besides, there’s not much point in having the back of the device more scratch-resistant than its touchscreen.)

- Ceramic materials are expensive.

- Ceramic materials are not as easily recyclable as other materials currently used for Apple product enclosures.

Let’s look at the issues in more details.

Mechanical properties

There are two important mechanical properties for an enclosure material:

- resistance to scratches,

- resistance to brittle fracture.

Scratch-resistance translates to hardness and for our purposes can be measured using the familiar Mohs’ scale, in which higher-ranking substances can scratch lower-ranking substances: diamond occupies the highest rank (10), next come alumina (Al2O3, aluminium oxide, called corundum, sapphire, or ruby depending on coloration and context) and few other relatively uncommon substances (9), and zirconia (ZrO2, zirconium (di)oxide) ranks 8 to 8.5. Consequently these materials are extremely unlikely to be scratched by something else, while the so-called scratch-resistant glass can be easily scratched for instance by sand grains (quartz, hardness 7). The hardened glass is situated somewhere between 6 and 7: harder than most steels (5 to 6). That’s why a glass touchscreen can’t be scratched with your keys or a knife, although it will collect tiny scratches from sand grains and other hard debris over time. Of course, it can also be scratched by diamond substitutes or a ceramic knife (both zirconia).

The aforementioned patent filing explicitly mentions two ceramic materials: zirconia and alumina. One has to wonder: Why not use a sapphire “crystal” for the touchscreen, where scratches have much higher visual, but also functional, impact? I suppose that the answer to why sapphire (which in the context of watch crystals means synthetic corundum, i.e. pure transparent alumina) hasn’t seen wide use in touchscreens lies in its high price and difficult recyclability, but before we get to this, let’s have a look at another important mechanical property.

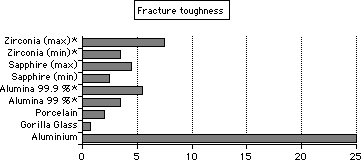

The experimentally measured resistance to brittle fracture is called fracture toughness and it is usually measured in MPa⋅m1/2. There is no popular relative scale (like the Mohs’ scale for hardness), but we can easily do our own relative comparison using values available on the web:

Rows marked with star (*) have a single source: this table from the manufacturer or ceramic goods Kyocera. Gorilla glass is a strengthened glass manufactured by Corning used in touchscreens. Other data come from various web sites, and while the values can of course differ based on purity, manufacturing process or test methods, I have tried to verify them from multiple sources and use a reasonable representative for the chart.

As you can see, Gorilla glass (or any other glass for that matter) compares poorly to the other materials, and while all of the high-tech ceramics (zirconia, alumina, and its transparent cousin sapphire) fare better, they are nowhere near plain aluminium. I did not include even tougher materials such as steel and titanium (values about 50 MPa⋅m1/2) to keep the scale reasonable. What does it mean? A high-grade ceramic enclosure is less likely to break than a glass one, but it still breaks easily: some of the materials break as easily as porcelain.

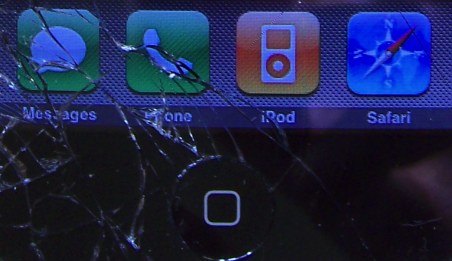

Incidentally, I dropped my iPhone on a setts paving last week (you can see the results below). I have already dropped my iPhone many times: it has often landed on its aluminium back or on one of the edges, additionally the steel bezel protects the glass when it’s dropped on a flat surface. A ceramic back would certainly decrease the survival rate.

Price

We are talking about an enclosure for a device that costs several hundred dollars. Frankly, I have a very blurry idea of what fraction of the price an enclosure can constitute, but at least some clues can be found.

If we look at iPhone replacement parts, the 3G back housing (made of plastic) costs at least $40, the glass with digitizer at least $35 ($60 for 3GS), and the original back housing (aluminium) $50. The manufacturing costs are certainly lower and differences may not correspond directly. My guess is that a relatively simple part made of aluminium, glass or plastic, costs less than $5 making it almost negligible. I may be wrong, but let’s look at the ceramics:

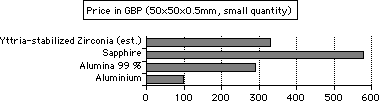

I have been able to find prices of the various ceramic materials on the web site of Goodfellow, a company that supplies various materials in small to medium quantities. These are not whole-sale prices and include shipping, so they are very different from the prices a phone manufacturer would get, but they serve well for relative comparison:

What makes these materials so expensive is their hardness, and hence difficult machinability. If the difference in a two pieces of aluminium (the metal) and alumina (the ceramic) sized roughly like the iPhone’s back and purchased as single items can amount to almost 200 pounds (about $300), I think that we can safely assume, that the difference for mass-produced parts could still be a few dozen dollars. Zirconia, is even harder and even more expensive. If you do not trust this comparison, try searching for the cheapest reasonably sized ceramic knifes.

While the iPhone is somewhat pricey, it is not a specialty device: people who buy it are willing to pay a premium, but not for a fake-diamond enclosure.

Environment

The last two years, Apple has accompanied all of its major products with environmental reports, so we know that “Mac mini enclosure is made of highly recyclable aluminum and polycarbonate,” and iPod touch features a “highly recyclable stainless steel enclosure”. While ceramic materials can in principle be recycled, grinding and melting them requires incomparably higher energy than grinding and melting plastic, glass or aluminium. In fact, aluminium is produced from alumina (which in turn is extracted from bauxite), but it is exactly this step that makes aluminium production so energy-intensive.

Ceramic materials are already found in small quantities inside many electronic devices because of their electrical properties, but to this point they have not been recycled, they go to landfill. I do not think that Apple wants its next flagship product to be less environment-friendly.

Conclusion

The idea of using zirconia or alumina (especially sapphire) for a touchscreen device is intriguing, but making a whole back side of a phone from it would do more harm than good. I can see two reasonable uses:

- a ceramic window for radio signal in a metal enclosure (quite likely),

- sapphire “crystal” for the front side of the device (less likely because of the price and recyclability issues).

Companies such as Apple file tons of patents, not all of which see use in production. Whatever the back side of the stolen iPhone prototype was made of, I do not expect to see a ceramic iPhone, or any other phone, in production. I believe that either the prototype had a plastic back (after all Gizmodo were not sure if it’s made of ceramic or plastic, although they could have had verified it easily), or it wasn’t the final design.